Thinking of our beloved brother on the 22nd anniversary of his passing and necessity demands our attention; when this interview was conducted in September 1994, Waylon Jennings had been commercially and artistically adrift for the better part of a decade. The swaggering country music maverick who knocked the wind out of Nashville 20 years earlier with a brilliant, raw-knuckled reinterpretation of the entire field had become an anachronism. They’d run him off, payback for innumerable transgressions. Formerly an unstoppable redneck titan, Jennings, tail between his legs, became a piteous creature. Since kicking drugs a decade before, he’d been an empty shell and in 1992 publicly announced that he would never again record. “Waylon’s lost his guts,” was the grumbled refrain amongst country music insiders.

“The people at Epic had so much as told me that they couldn’t sell my records,” Jennings said. “I kinda let them dictate to me that radio didn’t want to play me, that people didn’t want to hear me sing anymore and they figured it was all over for me. I said, ‘If that’s the way it is, that’s the way it is. Maybe it is all over.’”

This weakened condition, of course, proved temporary. RCA, Jennings’ label during the Outlaw glory days, eventually wooed him back for Waymore’s Blues (Part II). Produced by artistically bankrupt weakling Don Was, the disc was as unconventional as anything Jennings had tried before. Recording with a Was-assembled band of players from the Mellencamp and Petty bands, anchored only by Waylon himself, it was essentially a synth and effects-laden jam, loose, atmospheric but far from engaging.

Jennings was in Los Angeles to ballyhoo the album, holding forth in a plush suite at Ma Maison. Looking more robust, fit and trim than the former full-time hell raiser had a worldly right to, Waylon’s guileless, gregarious personality hardly measured up to a devilish, whiskey-bent reputation. But, as he frequently said, “If I’d done everything that people said I did, I’d weigh 30 pounds, be 150 years old and look like a gutted snowbird.”

Was attempted to provide the disk a theoretically fertile setting. “Don said, ‘Why don’t we do this as an impressionistic painting?’ That just knocked me out. I went in there and told them ‘Forget everything I ever did, just play what you feel. I’ll tend to being Waylon, you just concentrate on playing music.’”

Even with a present and dedicated Jennings, it was a complete misfire—aimless, static, artificial, hobbled by an imbalanced sound that, as they say in Nashville, “just lays there and bleeds.”

This was difficult to accept, particularly given the anticipation raised by the Waymore’s Blues title. That invoked a standard—a direct reference to Jennings’ highest artistic flowering, a classic song on his 1974 masterpiece Dreaming My Dreams.

The original “Waymore’s Blues” was stunning, a thickly acoustic, deep-grooving statement that defined and questioned his artistic persona. Fraught with swashbuckling Jimmie Rodgers blues, snarling, wry, a little dirty and a lot philosophical, it was Jennings at the top of his form.

With Dreaming My Dreams, Waylon had thrown down. When the needle dropped on opener “Are You Sure Hank Done it this Way?” and he sang “Lord, it’s the same old tune, fiddle and guitar, where do we take it from here? / Rhinestone suits and big shiny cars / we need a change,” it was a direct challenge that sent Music City USA up the nearest tree. Waylon was 37 when he wrote that, had been in the business for almost 25 years and damn sure knew what he was talking about. Change was coming fast then, mostly in the worst wrong ways: the Country Music Association did name Waylon best male vocalist but also made John Denver their Entertainer of the Year.

“’Are You Sure Hank Done it This Way?’ was about Nashville and the business,” Jennings said. “I was lookin’ around for change then, and here I was, accordin’ to them, lookin’ like somethin’ from outer space . . . probably did a little bit. And the funny thing is, all I was tryin’ to do was survive and at least try things my way, but they really thought I was out to destroy what they had.”

Waylon, the brooding, shaggy, black leather clad Texas hillbilly with a rock & roll upbringing, was on the verge of making country music’s final, great artistic breakout. With cohorts Willie Nelson and Tompall Glaser, through a wildly unpredictable subculture that became the Outlaw movement, he made that change. It was a period as tense and explosive as it was glorious and inspiring. “Along comes Waylon, with that long greasy hair, and he was just swarmin’, all over the place,” Billy Joe Shaver told me. “Tough old son of a gun. And people just lined the walls when Waylon recorded back then. Everybody knew he was gonna do somethin’, they didn’t know what, how or which way it’d go, but he was gonna do something.”

Risk was always seductive to Jennings. Even as a rocker, he was unconventional, debuting on wax in 1959 with his weird, Buddy Holly-produced, King Curtis fueled, primitivo en Francais stab at “Jole Blon.” As an aspiring folk-pop star under the influence of producer Chet Atkins, his 1969 version of Jimmy Webb enigma “MacArthur Park” earned that years Grammy for Best Country performance. Both reveal an idiosyncratic, minor-keyed blend of disparate elements characteristic of Waylon’s unorthodox musicality.

During his early 1960s crucible of a run at Phoenix’s deluxe honky tonk showcase JD’s, Waylon and his Waylors’ rhythm drunk, guitar mad style underwent a remarkable metamorphosis. The goings on in just-next-door Los Angeles, particularly those of the masterly Wynn Stewart and his aggressively progressive band (which featured Merle Haggard and steel guitar paragon Ralph Mooney), grabbed ahold—“I taught myself to play guitar so it sounded just like Mooney’s steel,” he said. In Jennings hands, Mooney’s rolling, minor chords evolved into an increasingly angular, steam-heated, swampy approach. The full-blown Waylon sound—a gutbucket redneck-funk style unlike anyone else’s—was codified when he added Mooney to the Waylors around 1971. The music positively erupted. It was a natural and completely radical evolution.

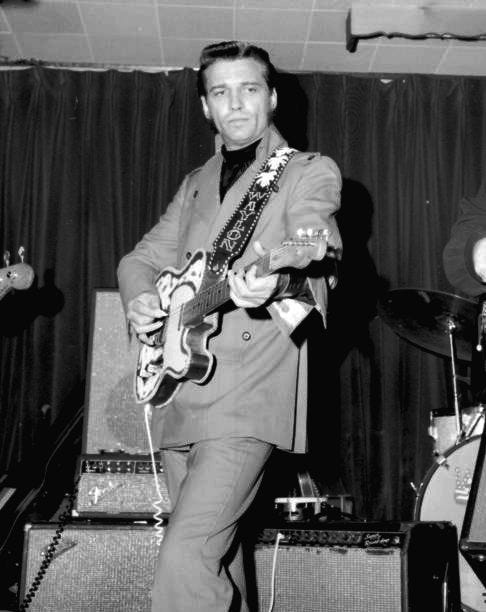

No less unusual was the Jennings image. Having long since tired of standard presentation (he started performing in 1949, leading radio band the Texas Longhorns at age 12), by ’69, Jennings and his band sported severely mod outfits and matching black leather guitar straps with WAYLORS spelled out in chrome studs. The heavily pomaded star wore exaggerated double-breasted gangster suits or sharply tailored, real-now tuxedos abundant with ruffles and braid. The title of the sole hillbilly exploitation flick Waylon starred in, 1967’s Nashville Rebel, could hardly have been more appropriate.

Country music wasn’t happy with what Waylon represented and let him know it. “I got that from people like Carl Smith and Faron Young,” he said. “When I first came to town, these son-of-a-bitches like to drove me nuts. Faron used to call me ‘Greaser’ cause my hair was slicked back and Carl, who was one of my heroes, if I ever said something nice to him, would say ‘Don’t be sayin’ that. Who do you think you are? What do you think you’re doin’ here? You think you can sing? Get outta here!’”

At RCA, Chet Atkins recognized Jennings vast potential, but the label hated his rhythm heavy mixes. “I wrote so on the bottom,” Jennings said. “The fuel of my records is in the bottom. And I used to have real shit with the people who worked for RCA. When I’d want to put the bottom in, the bass and drums, the engineers would say ‘You can’t do that—it’ll make the record skip!’ They were tryin’ to do everything they could to keep me from makin’ it—and when I say that, I mean the system in Nashville. And I still really don’t know how to deal with that: people with ego problems. I’ve got as big an ego as anybody, but I had to learn how to channel that in a different way, to put it into the music.”

Waylon’s arrangements were provocative, unusual. Using everything from bowed bass fiddle to a hairy wall of acoustic rhythm guitars, his records were sculpted, full of open space and unfolding steel and guitar dialogue, leavened by vocal snarls and whoops. They were raw, compelling, thoroughly country vehicles for his magnetic, updated version of the folk rounder/troubadour/vagabond persona.

In 1974, Waylon went over Nashville RCA’s collective head and dealt directly with the label’s New York executives—a kick start of the Outlaw movement. After landing a production deal (the artist is given a free hand, obliged simply to deliver completed masters), he became the first country artist to openly challenge the previously unassailable Nashville protocol.

“They really went crazy about that,” he said. “I had this production deal, but I saw that I was still under their thumb, because I’m in the studio and they still had control—these damn engineers were callin’ upstairs to the office, to the head of RCA, tellin’ ‘em what was goin’ on. They did not want me to succeed. It was a battle: when I wanted to try somethin’ they wouldn’t let me.”

Required to use RCA studios due to a binding engineers union contract, Jennings instead cut “This Time” in Tompall Glaser’s studio, with Willie Nelson producing, Kyle Lehning engineering and nobody telling him what to do. When RCA refused to release it because it would break the union contract, he told them “That’s all you get. I ain’t recordin’ anything else.’ They knew, and they released it. Consequently, it was my first #1 single and album.”

Come to find out, just like ole Samson in the Bible, he’d torn down the Temple in a cataclysm of artistic audacity.

“And, of course the union, well, that broke the whole deal, broke it right there. And all of ‘em, RCA, CBS, had to sell their studios. I tried to go over and buy one of ‘em, and Chet Atkins laughed at me, he says ‘You’ve got the nerve of Hitler! You’re the reason they’re sellin’ em, and you want to buy one?’ They wouldn’t sell it.”

He never played their game: “I could’ve made deals a long time ago to get the awards—just show up, I was told. ‘If you come [to the ceremony] you’ll win most of the stuff’ on several different award shows. I never really went for that at all. It’s the platinum and gold records on my wall that I treasure because the people cared enough and laid down their money for ‘em.”

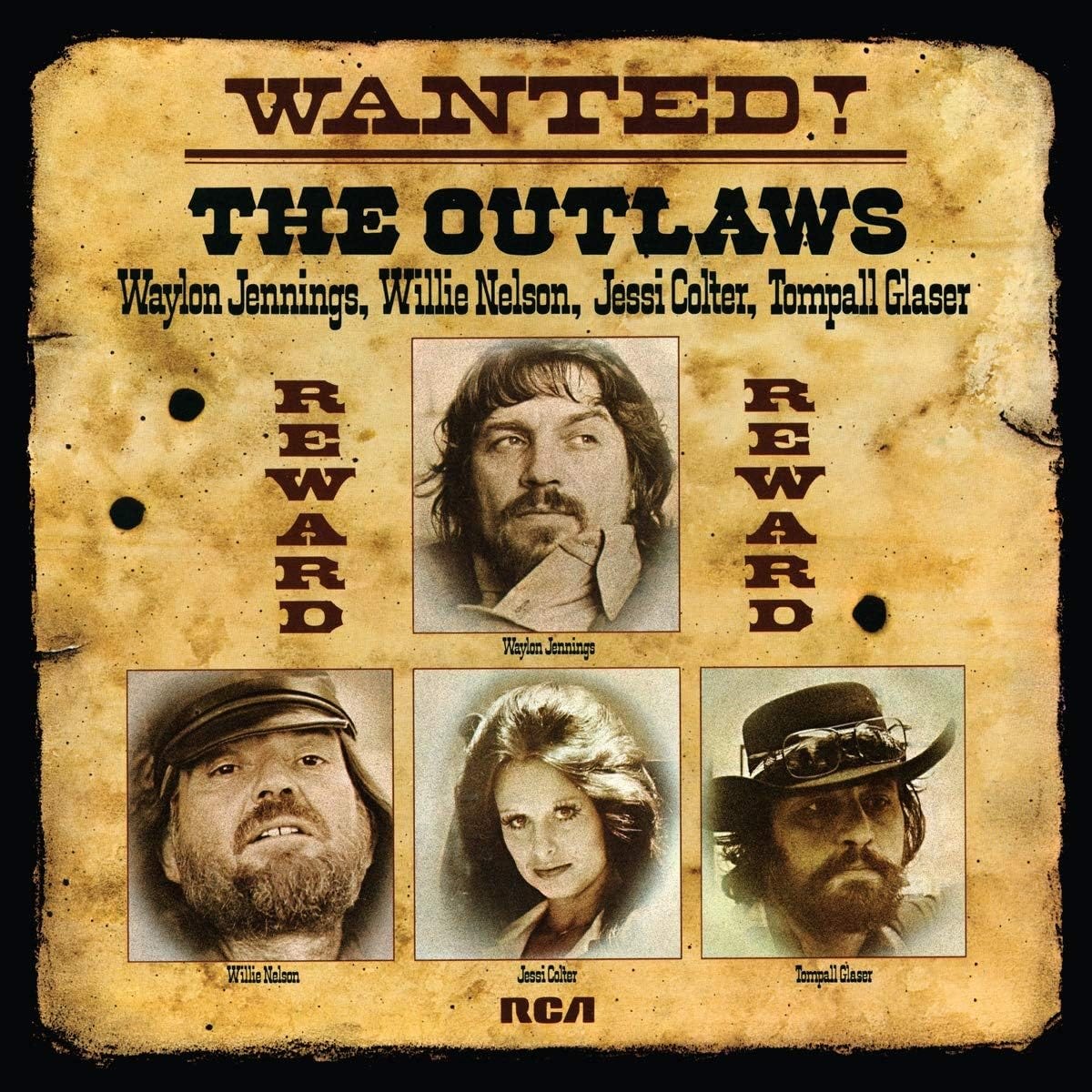

By this time, Jennings could do whatever he wanted with his music. The result was Wanted: the Outlaws (a compilation of tracks by Jennings, his wife Jessi Colter, Nelson and Glaser), which became, in 1978, the first certified platinum selling country album to be recorded in Nashville (Cash had beat ‘em to the punch—and outsold the Beatles—with his Folsom and San Quentin LPs).

The whole Outlaw bit exploded with the greatest popular ferocity that country had seen since the days of Hank and Lefty slugging it out in Billboard’s Top Ten; Waylon’s Greatest Hits went quadruple platinum and there must still be millions of people sick to death of “Luckenbach, Texas” and “Mamas Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up (To Be Cowboys).”

After “speeding his young life away” for the previous decade plus. Waylon went absolutely apeshit hog-wild when cocaine hit Nashville circa 1975. Stories of his escapades and brawling are some of the best—and wildest—told in Nashville. But he was careless—blowing it, coasting and ultimately falling. He knew it and in 1984 finally quit drink and drugs on his own, without any formal medical intervention.

“I didn’t even know who I was or what I was,” he said. “When you spend that many years on drugs and you get off, you don’t even know how to walk into a room or what to act like . . . You have to learn everything all over again.” Following triple bypass surgery, he climbed uneasily back into the saddle but rarely came up with a hit. Eventually, he split from RCA, foundered at MCA, left, then quit Epic after three albums.

Jennings came to terms with it all in 1992, as his “Hank Williams Syndrome” made painfully clear. “Rambling about down through the South, I find things are changing a lot / Especially me, it’s easy to see, Montgomery [Alabama}’s still hot / and I’m not” was an extraordinary admission of failure.

“I don’t mind sayin’ that. It’s the truth,” he said. “A bunch of new things were comin’ along and I’d had my day.”

Blunt, boldly individualistic, he was peerless, both a flabbergasting fount of raw power and an unrivaled commercial succses. While his vocals, musicality and gifts as a writer perhaps never did overall best either his historic forebears or his closest competitive contemporaries (Nelson, Jones, Haggard, Killer, yes, even Coe and Paycheck), Jennings’ unparalleled achievements and impressively ill-considered missteps were the epitome of the modern country music experience—trumping even jailbird Haggard’s mind-bogglingly exceptional artistry. Where Hag was dark, sullen, often downright mean, Waylon’s personality, his carefree, vagabond charm and nonchalant charisma, was wholly irresistible.

Haunted by that crucial alliance with Buddy Holly (Buddy: “I hope you freeze your ass off on that bus.” Waylon: “Well I hope your damn airplane crashes!”), Waylon’s cultural place and spiritual cachet within the universal curl—where rock & roll and country rattle the laws of spiritualism and physics—is wholly unique, representing a God-given obligation and duty which he dazzlingly discharged.

Back at Ma Maison, he began speaking in the past tense.

“The whole thing of it is, I never had a goal in my life. I really considered myself an overachiever, never thought I’d get that far. I thought they’d starve my ass out of town.”

Waylon developed diabetes and died eight years later, at his Chandler, Arizona home, on February 13, 2002. He is buried in Mesa, Arizona. Rest in Peace, Hoss.

Ah, Andy--ever the surgically precise, impeccable zinger of an editor! "Imbalanced' meant more as regards the productions pathology, which means I should've chosen "unbalanced!" No love lost for Don Wasn't, but I will listen. As ever, thank you for reading!!!