Over a forty-year career researching and interviewing country musicians, one can’t help but form some after-hours alliances that tend to dredge up a few sticks of deep insider dynamite. Here’s a clutch of lurid tales, some perhaps apocryphal, others eyewitness verified accounts courtesy of roadies, rockers, radio men and one certified Country Music Hall of Famer, involving sequin-spangled protagonists Roy Clark, Ricky Skaggs, Keith Whitley, Faron Young and Lefty Frizzell. Let’s start with Ricky Skaggs:

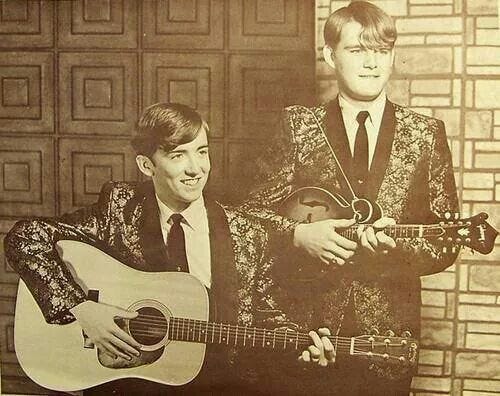

The Kentucky-born bluegrass multi-instrumentalist Skaggs was a highly significant force in that genre, one who was picking mandolin at age 5, appeared alongside Bill Monroe (an infamous, er, magnet for juvenile prodigies) at 6 and by 1970, partnered with the brilliant Keith Whitley, was invited to join Dr. Ralph Stanley’s Clinch Mountain Boys, a top tier gig, to put it mildly.

As a single in the early 80s, Skaggs was riding high, reaching a popular and commercial altitude no other bluegrass musician has yet rivaled. With Epic Records behind him, three of his LPs went gold (at the time, few country artists made that grade) and his 1982 Highways & Heartaches sold platinum—an impressive feat which significantly prepped the market for soon-to-rise New Traditionalists George Strait and Randy Travis; Skaggs’ appeal was so broad that NYC mayor Ed Koch cameoed in Skaggs’ “Country Boy” video.

Releasing 5 albums in 4 years, the kid was on a prodigious roll, but there was a sudden, disastrous rupture in the Skaggs momentum, which plunged into the ditch before the musician reached his 30th birthday.

He virtually disappeared for a time and one night, up in a Bakersfield joint working with Rose Maddox, I found out why—she said the story went that a civilian or, worse, a journalist, had wandered onto Skaggs’ bus and caught him in flagrante delicto with one of the boys in his band. Word of this alleged bluegrass buggery spread through the country set like a gain of function virus and the musician, so the rumor claimed, was thoroughly disgraced and had to publicly apologize to the congregation at his church (but this has never been proven) and Skaggs, despite a long and very distinguished career, has never able to replicate that historic success

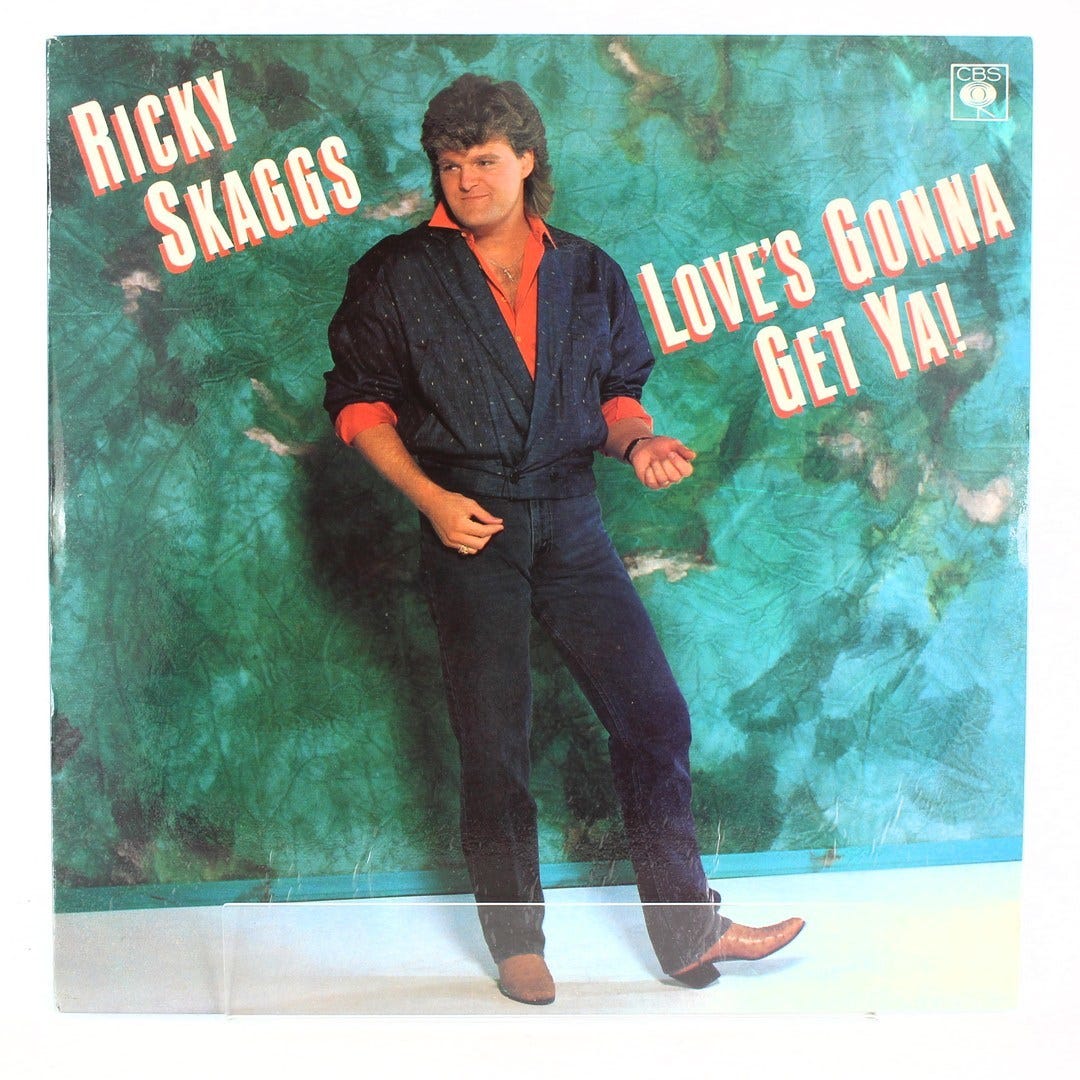

2 years dragged by before Epic finally issued a new Skaggs album, the non-unironically titled Love’s Gonna Get Ya. Sample title track lyrics: “When you least expect it, love will put you in your place . . . and pay you back for all the times you left it in disgrace.”

Skaggs’ former partner, Keith Whitely, was as talented and popular as he was damaged, and one wonders how much of that was due to a childhood spent thrust into the problematic, long entrenched bluegrass culture of wunderkinder exploitation—Whitley won his first talent contest at age 4. He was an exceedingly gifted artist and vocalist of perfected sensitivity who charted multiple #1 hits, but he had a terrible drinking problem.

While Whitley famously married country singer Lorrie Morgan in 1986, he’d previously wed the Kentucky-born Kathi Littleton, a union which came apart in spectacularly debauched fashion, as singer and then-Nashville resident Jimmy Angel recounted. The late country star Jim Reeves’ widow, Mary, had taken Angel under her wing and he spent a lot of time hanging out at the (now defunct) Jim Reeves museum.

“Keith Whitley? He was like Jekyll and Hyde when he drank,” Angel said. “He was a mean drunk, boy. And vicious!”

“His first wife, Kathi, was working at the Jim Reeves Museum and one afternoon Whitely showed up, drunk. He grabbed Kathi, dragged her out to the back parking lot, threw her on the trunk of his car. He was yelling and screaming, completely stripped her clothes off and started beating her, yelling the whole time. Mary Reeves and the guys stepped in and she kicked him off the property.”

“Last time I saw Whitley was at Shoney’s,” Angel said. “I was having lunch with Harold Bradley, Ray Price, Faron Young and Mary Reeves. And all of a sudden, here comes Keith and he goes down, fell flat on his face, and then he starts crawling across the floor . . . Mary told him ‘Son, you better get straight or you’re going to die.’”

Not long after, he did indeed perish from alcohol poisoning at age 34. Autopsy results put his BAC at 0.47—a shocking figure. It was a stunning tragedy and an incalculable (albeit inevitable) loss to country music.

Jolly Joe Nixon, an imposing 6’ 5” ex-Marine who survived the Bataan Death March and became a key force in post-war country radio, was a pal I frequently interviewed and hung out with. Broadcasting since 1949 in hometown Knoxville, Dallas and, later, at Los Angeles’ KXLA, KRKD, KIEV, KWOW, Jolly Joe was an irresistible character, one inevitably befriended by the biggest names in the business.

Visiting with Joe one afternoon, I asked about Lefty Frizzell. When the honky tonk genius moved to California in 1953, he was renting a hillside house in leafy La Canada Flintridge, not far from the Nixon digs.

“I went over there one day,” Nixon said. “And Lefty was sitting at his kitchen table with a bottle of whiskey and a box of triple ought gelatin capsules, the biggest size they make.”

“I asked him, ‘Lefty, what are you doing with those?’”

“Well, you know, after the show I’m always signing autographs, but I really want a drink and I can’t do that in front of the fans. So, I figured I’d just fill up a bunch of these capsules with whiskey and tell ‘em ‘oh, excuse me, it’s time take my vitamins.’”

“So he’s sitting there, pouring booze into these capsules and fitting them together, going on about what a great idea he had, and laughing about ‘taking my vitamins’ and as time went by, of course, the alcohol began to melt the gelatin and there was just a big puddle of goo in front of him. And he looks at me and says, ‘Well, I guess it wasn’t such a good idea after all.‘”

As he related this, Jolly Joe was standing over the engine of his daughter’s vintage, Ford Falcon Ranchero, pouring gasoline from a battered red can onto the carburetor—with a lit cigarette in his mouth. He began roaring with laughter, repeating “‘It wasn’t such a good idea!’”

That’s country, hoss.

Country star Faron Young (“Sweet Dreams,” “Hello Walls”) was infamous for his hot-blooded impulsiveness and wild, oft disruptive behavior (he and George Jones had no less than four separate fist fights over the years). The most notorious incident was his 1972 public spanking of a little girl who’d refused to join the singer on stage while he performed his current hit “This Little Girl of Mine.” Young claimed the 6 year old had spat at him, for which she was turned over his knee and, er, disciplined—in front of her parents and hundreds of others. Incredibly, the stunt cost him only a $3,500 civil settlement, a $24 fine and $11 in court costs, but it was the first significant dent to his reputational skull. Many others followed.

Young was a transformative force in modern country, redefining the drinking song with such sleek, emotive accounts of dipsomaniacal darkness as “Pour Me a Tall Pair of Crutches” and “Wine Me Up” and plumbing the bleakest despair with his classic hit “It’s Four in the Morning.” But by the 70s, Young’s erratic behavior was catching up with him. On the road in Canada, he’d supposedly gone into a blackout rage and held an entire diner at gunpoint; back home in Nashville, he’d get obstreperously obnoxious, “I saw David Allan Coe and Faron get into it one night,” Jimmy Angel said. “Faron kept bugging him and Coe finally grabbed him by the neck, picked him up, lifted him clear off the floor and told him “Leave . . . me . . . alone.’ He left him alone!”

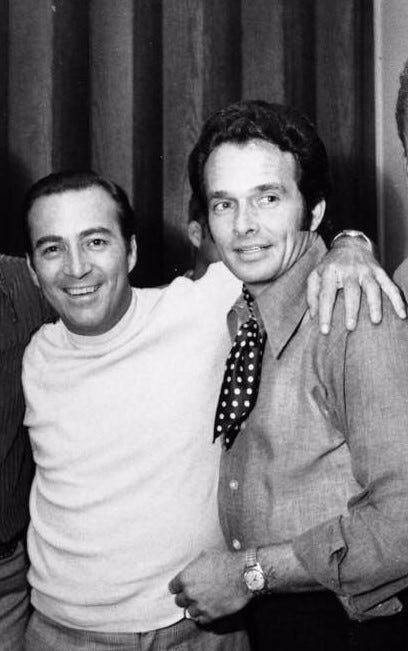

Merle Haggard was one of Young’s biggest fans. While interviewing Hag at his Palo Cedro compound in 1998, Young’s name came up and the Hall of Famer had some choice recollections of Faron.

“I really liked him, he was a fine singer, but he could be . . . mean,” Haggard said. “I remember one night after his show, Faron was visiting with the fans and after awhile he clearly wanted to get away. I was standing there with him and all of a sudden he shouted ‘I don’t sign autographs for FAT LADIES!’ That was just plain embarrassing.”

“He started having trouble getting work, so I put him on my show. One night, we were all on the bus, I had my son Marty with me, he was recovering from a gunshot wound to the abdomen and Faron started in with him, I don’t know over what, but finally, for whatever reason, Faron punched him and reopened the wound. I had the bus pull over, put him out with all his stuff and we left him on the side of the road. I still feel kinda bad about it—that was the last good job he ever had.”

This was circa ‘77-78 and Faron went into an agonizingly slow-motion tailspin, shooting up the family home’s ceiling in 1984 (which resulted in a divorce) and jumping from major labels to small Nashville indies. He developed emphysema and could no longer deliver a creditable vocal performance, forcing retirement. The ultimate result was his 1996 suicide by gunshot, or as word had it at the time, gunshots (plural) to the head. Even then he lingered on another day in hospital. At 64, he’d fulfilled the promise of his first #1 hit, “Live Fast, Love Hard, Die Young (and Leave a Beautiful Memory.)” RIP, Wampus Cat.

As sick, sad and sorry as these episodes were, we’ve left the absolute rock-bottom, everloving freakshow worst for last. Our source on this one was a storied, professional roadie widely known in rock and country circles, the inimitable, late great Texas gear slinger Bondo, who did a fair stretch working for a Country Music Hall of Famer and beloved syndicated TV co-host whom, we can safely say, possessed the most legitimate shit eating grin in the business.